Nasa plans to launch a rocket to the moon next week in an effort to finally land humans there after a gap of 50 years.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of mission management at the US space agency Nasa giving the final approval for what would become humanity’s most recent voyage to the moon. Few anticipated at the time that it would be more than half a century before Nasa was ready to return, even Apollo 17 commander Eugene Cernan, who believed as he went back into the lunar module in December 1972 that men would return “not too long into the future.”

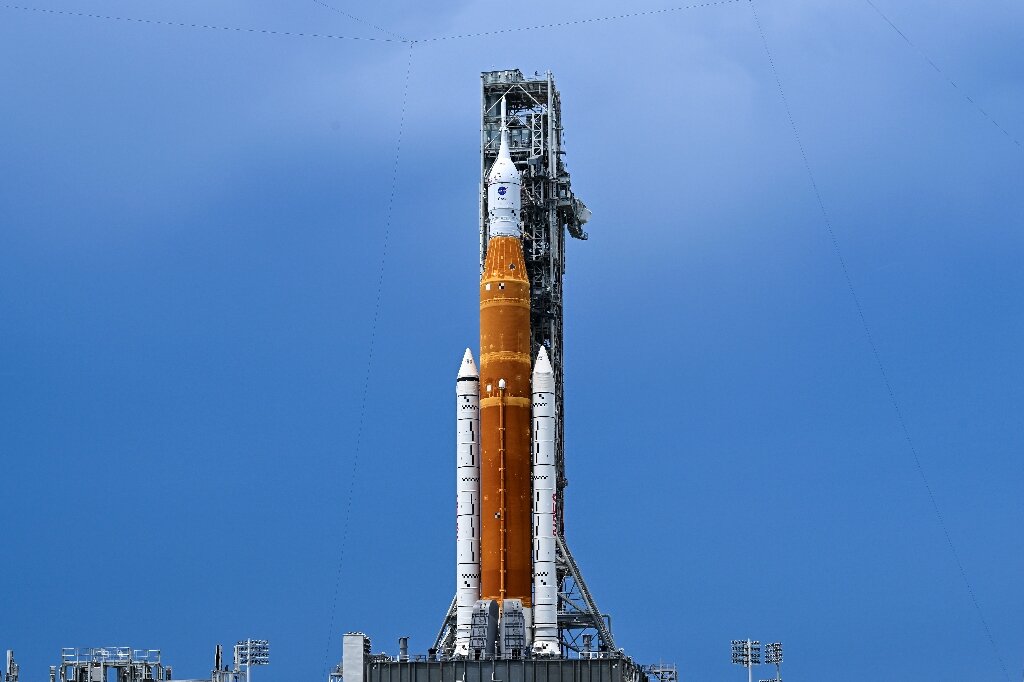

Artemis 1, the most powerful rocket ship in history, will attempt to close that decades-long gap four minutes after midnight Wednesday, despite late technical difficulties and Florida’s weather gods.

The Orion capsule will not carry humans on its 25-day, 1.3 million-mile journey to and from the moon, but its success will open the way for a crewed landing effort within four years. Artemis 3, scheduled for 2025 but likely pushed back a year, will add a woman’s name to the only 12 moonwalkers in history, all men from the Apollo missions between 1969 and 1972.

“We’re going back to the moon after 50 years to stay, to learn to work, to create, to develop new technologies and new systems and new spacecraft in order to go to Mars,” Nasa administrator Bill Nelson said in an interview with Newsweek earlier this year, explaining the purpose of the Artemis program.

“This is a historic turning point.”

After a series of delays during the summer and early fall, the space agency is hoping that things will finally come together for Wednesday’s launch. Attempts in August and September were abandoned because engineers identified an engine cooling issue and were unable to repair an unrelated fuel leak.

The threat of Hurricane Ian caused the space agency to roll the massive $4.1 billion Space Launch System (SLS) rocket back to the safety of the hangar, putting an end to hopes of an early October launch.

In the midst of Hurricane Nicole’s 100mph wind gusts, some questioned Nasa’s decision to leave Artemis exposed on its Cape Canaveral, Florida, launchpad.

This storm caused a two-day delay until Wednesday, as well as a thorough post-hurricane inspection by engineers at the Kennedy Space Center before it was declared fit to fly.

“If we didn’t design it to be out there in harsh weather, we picked the wrong launch site,” Jim Free, Nasa’s associate administrator for exploration systems development, said at a press conference on Friday.

Delays, according to Nelson, a former space shuttle astronaut, are “part of the space business.”

“We’ll go as soon as it’s ready.” We don’t take off until that time, especially not on a test flight. “We’ll make sure it’s right before we put four humans up there,” he said following the September scrub.

These humans will be aboard Artemis 2, a 10-day interim mission scheduled for May 2024 that will take astronauts beyond the moon without landing to test new life-support systems and equipment designed for long-duration spaceflights.

Artemis 1’s “crew” includes sensor-rigged mannequins Helga, Zohar, and Moonkin Campos, who will measure radiation levels, as well as a soft toy Snoopy and Shaun the Sheep as gravity detectors.

“We’ll never get to Artemis 2 if Artemis 1 fails,” Free explained.

Nasa’s reasons for wanting to return to the lunar surface have evolved as technology has. The agency is looking beyond the Apollo era’s brief exploration visits to establish a long-term human presence, including the construction of a lunar base camp, as the foundation for crewed missions to Mars by the mid-2030s.

Nasa’s stated goals for the “Artemis generation” include scientific discovery, economic benefits, building a global alliance, and inspiring a new generation of explorers.

The Artemis program is part of Nasa’s Moon to Mars vision, which includes bringing in international and commercial partners to deep space exploration, including Elon Musk’s SpaceX and heavy lift Starship rocket, which could be ready for its first orbital test flight as soon as next month.

The goal to maintain the US ahead of Russia, and especially China, in the next phase of human spaceflight, is unspoken.

Analysts, including Nasa’s own inspector general, believe the $93 billion price tag for the Artemis program, which includes $4.1 billion for each of the first launches, is unsustainable. They point out that it is already billions of dollars over budget and years late.

However, other analysts believe that the moon to Mars initiative will be fully funded even if Republicans grab the House and the nation’s purse strings from Democrats after the final November election results are in.

“The support coalition is bipartisan and much more tied to constituent interest.” “There is political support,” said John Logsdon, founder of George Washington University’s Space Policy Institute.

“[But] so many things must happen before the first Mars landing mission is feasible that all you can say is, yes, we will send humans to Mars if everything goes as planned.”